FLINT – Adorned in her usual Sunday hairnet and ruby red kitchen apron, Aurora Sauceda eagerly waved at each family that packed into the bustling San Juan Diego Activity Center following 9 a.m. Spanish Mass.

“I just feel the warmth. . . . Here, everybody comes together,” Sauceda said with a bright smile, surrounded by steaming plates of pupusas and Nopales con Huevo. Amid the giggles of young children in their Sunday best, this is a community that has supported its members despite a water crisis response that failed and continues to fail them.

With roots in Flint, Texas and Mexico, Sauceda serves as the community coordinator and driving force for Latinos United for Flint, or LUF. Formed in 2016, LUF was born out of the water crisis to assist the Hispanic community – both documented and undocumented – with health services, immigration concerns, nutrition and housing. And while it’s been more than 10 years since polluted water flowed through the pipes of this mid-sized city in southern Michigan, the after-effects of what was billed as the state’s worst public health disaster are still felt in the small but tight community of Hispanic residents, many of whom did not speak fluent English at the time. And many of whom continue to feel marginalized by a local government that seems to overlook them.

“They were more vulnerable. It makes me wonder how they are faring now,” said Karen Weaver in a recent interview about the city’s Hispanic community, then and now. She was Flint’s mayor from 2015 to 2019. “Those are some stories that we don’t know if anybody has heard. I haven’t heard them, and I’m right here. So - who has heard their stories?”

On April 25, 2014, the city of Flint switched the city’s water source from Lake Huron, as supplied by the Detroit Water & Sewerage Department, to the Flint River.

Engineers determined at the time that the city would have to spend $50 million to get the local 1950s-era water treatment plant up to code to make the water safe. Instead, facing a financial crisis, city managers invested only $4 million. The result: Millions of gallons of water with unacceptable levels of sodium, lead and other contaminants were pumped for about 18 months into the homes and businesses of thousands of residents.

While people complained about dirty water and illnesses almost immediately, the state, under former Gov. Rick Snyder, didn’t declare a state of emergency until Jan. 5, 2016. Afterward, in an attempt to mitigate the damage and deliver water to thousands of ailing and angry residents, water distribution centers were set up.

But to ensure “it was just Flint people that were getting services,” a form of state-issued identification was required to obtain water, said Jim Ananich, former minority leader of the Michigan Senate and current board member of the International Center of Greater Flint, an organization that offers support services to Flint’s cultural communities.

This decision marked one of the first blows to the Hispanic, non-English-speaking and undocumented population in Flint, Ananich said, as it illustrated a disregard for their welfare.

The first problem was many of these residents were afraid to present their IDs for fear of being detained and deported. So, they couldn’t collect water at the centers.

Secondly, more than 270 Guardsmen along with the American Red Cross and local law enforcement delivered water and filters to over 22,000 homes. Despite good intentions, aid-canvassing while dressed in military garb and badges did not serve as an effective response. For the undocumented community especially, this emergency response again generated fear.

“It’s unsettling to have this military presence coming up to your door, or law enforcement coming up to your door, when there’s just that whole history for people of color in the country,” said Asa Zuccaro, a Flint local and executive director of the Latinx Technology and Community Center on the city’s eastside.

These fears fell against the backdrop of the Obama administration that had already deported millions of people from the U.S. In fact, just two weekends before, the administration announced a nationwide, concerted effort for the deportation of Central American immigrant families, including mothers and children.

When two weeks later Michigan Guardsmen arrived at the doorsteps of immigrant families with a knock and carrying cases of water, “some of them would not answer the door. . . . They were afraid,” Sauceda said.

Because of these factors, an entire segment of the population “that just is under the radar and also needs it” was largely missed, Ananich said.

Seen but unheard

Recent U.S. Census numbers put Hispanics in Flint at 4.5% of the population, or about 3,600 people. If water was the crisis point for them a decade ago, today’s fears, like so many across the nation, center on government hostility and neglect for their welfare.

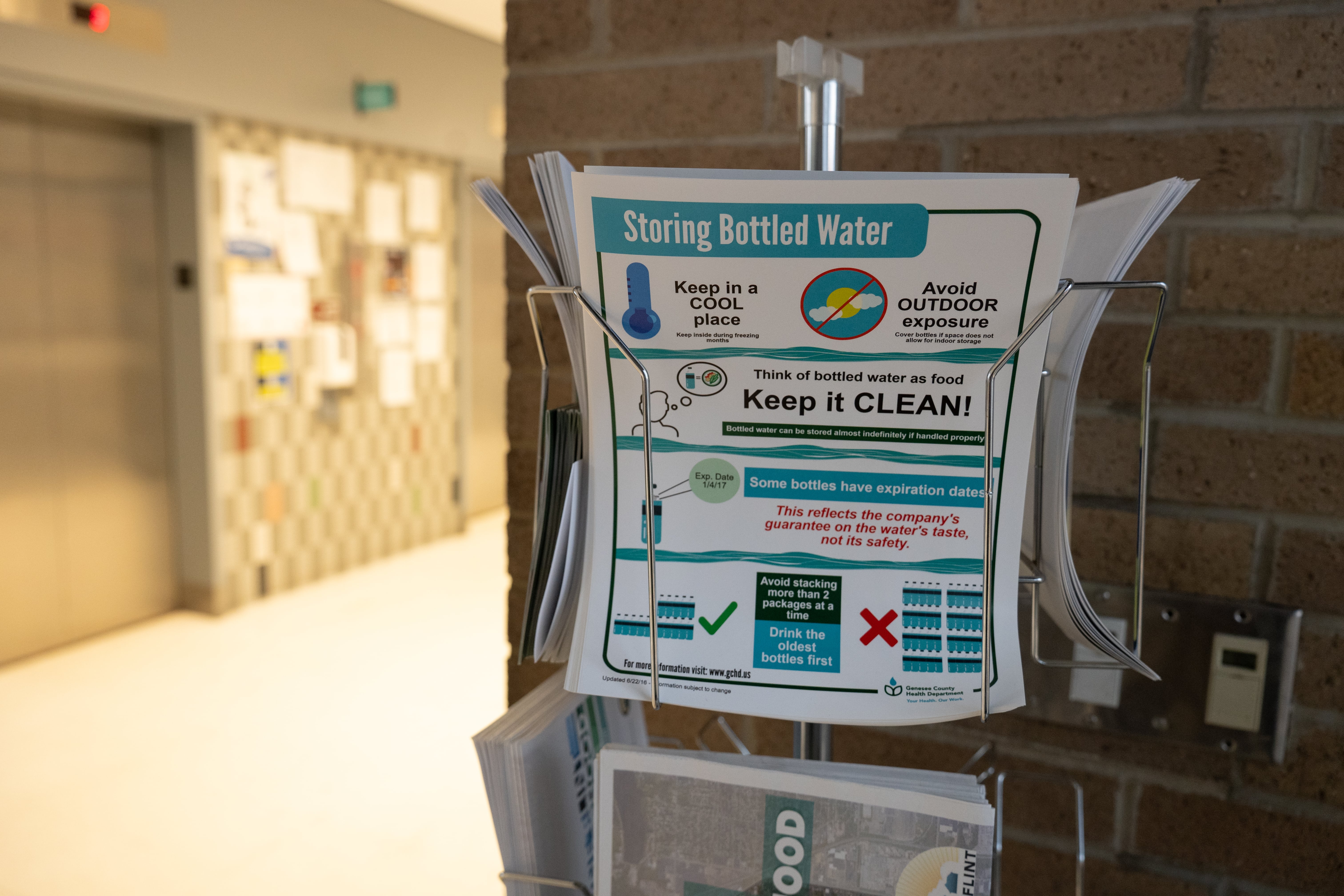

In the absence of trusting government for help and protection, many among Flint’s Hispanic population have turned away from official channels to community centers such as Our Lady of Guadelupe Catholic Church and the Latinx Center. For example, in 2018, when the state-funded water distribution centers were closed down, local foundations such as the Community Foundation of Greater Flint sponsored water hubs. And in 2019, Our Lady of Guadalupe received $10,000 from the United Way to purchase and distribute water to the Hispanic community on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays from 4 to 6 p.m. On one day alone that summer, Our Lady dispensed 486 24-packs of water to 133 families.

The larger community was not always supportive of targeted efforts such as these. “People found out and they said we were discriminating because we were not handing out water to other community people,” Sauceda said. “They were making comments that it was just because ‘we’re not Hispanic and we don’t speak Spanish.’ . . . Can you believe that?”

Beyond concerns over deportation and water distribution sites themselves, the Hispanic community was facing another issue: the barrier of language accessibility. Nearly all public communications related to the crisis at the time were delivered in English.

“Our Spanish-speaking and undocumented communities were really in the dark for a long time before they found out about the water crisis,” said Sauceda. “The English speakers were aware of it, but the Spanish speakers weren’t aware of it because they didn’t know what was going on. We had a case of a young lady who was pregnant while that happened. And her baby was affected by it.”

Some did not learn of the potentially lethal water contamination until April of 2016, two years after the switch from the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department to the Flint River and three months following Snyder’s declaration of a State of Emergency.

“There was no policy maker that was concerned about, ‘do we need to translate things into Spanish?’ That all had to happen through grassroots advocacy,” said Emily Feuerherm, a linguistics professor at the University of Michigan-Flint. “This idea that this city is American, this city is English-speaking with some white people. It totally erased this entire other population and group of those with an immigrant background, multilingual background.”

Beyond the Hispanic community, 2.9% of Genesee County speaks languages other than English and Spanish in the home, such as Asian and Pacific Islander, Indo-European and other languages.

The language barrier persisted past the Hispanic community’s discovery of the crisis, as there was an additional burden in receiving financial benefits from the state.

On Feb. 24, 2016, Snyder announced the Michigan State Legislature’s approval of a $30 million aid package that included a provision to pay back a portion of people’s water bills, as well as pay back for the significant cost of buying water for drinking, cooking and bathing. But once again, residents only received information about applying for these mitigations as part of their utility bills. Those instructions were only explained in English.

“They would have to call in and leave a message and because they were leaving a Spanish-speaking message, they didn’t understand it [in the office], so nobody would get back to them,” Sauceda said.

Similarly, a month later, seven affected families filed a class action lawsuit, claiming that government officials were aware of the increasingly dangerous levels of lead in the water. Following defendants’ attempts to dismiss the suit, the Michigan Supreme Court ruled in July of 2021 that plaintiffs could continue with the litigation. This culminated in an approval of a $626.25 million settlement in November 2021 with more than 90,000 claims within the city of Flint.

In order to become a claimant of the settlement, residents had to apply with supporting documentation by June 30, 2022.

However, “all the applications were in English,” Sauceda said. “So, they didn’t know how to fill them out. . . . I would say that hardly any of our undocumented, our Spanish people, got to even apply for the lawsuit.”

And again, the same happened with applications for the Flint Registry, a community tool created to connect those affected by the water crisis to necessary resources. Applications were in English. An interested participant had to call the registry to request a Spanish version.

“And I will be very honest, a lot of that is a funding situation in that sending a letter with all of the translations is a significant weight,” said Felicia Eshragh, program manager of the Flint Registry. “If you would like it to be translated, we can go from there.”

Of the 22,259 registrants within the program as of January 2025, 4.4% or an approximate 979 identify as Latinx or Hispanic, marking a potential impression upon the community but certainly not in its entirety.

Also, English as a Second Language (ESL) services within the city reflect what some call dwindling attention and indifference. In 2015, Feuerherm spearheaded an ESL mapping project of the county, documenting a total of nine ESL programs within and around Flint. Of those nine, four no longer offer programs.

“There was absolute invisibility,” said Feuerherm, who is also a member of the International Center of Greater Flint. After conducting the assessment, Feuerherm came to understand first-hand the neglect people feel.

“People would come up to me [and say] ‘Thank you so much for talking to me. I have wanted to share ideas but haven’t ever had the opportunity,’” she repeated. “’Nobody seems interested.’”

‘Maybe We’ll Do Better’

There has been good news too. The city of Flint now has four “navigators” in the Office of Public Health who are tasked with bilingual services. This mitigation was established in 2020.

“The public health navigator position was established within the city of Flint's Office of Public Health as a direct response to the multifaceted challenges that emerged from the Flint water crisis,” said Shana Rowser, communications manager for the city, in an email. She went on to acknowledge that the Hispanic community faced “unique challenges” during the crisis when “language barriers and fears related to immigration status led to reduced access to vital information and resources.” The new navigators are all fluent in Spanish to help with official communications. Also, the city no longer requires documentation to access resources as a way to assure residents they can ask for help “without fear,” said Rowser.

Despite this effort, Spanish speakers are still skeptical of their government and instead have redirected their focus to within their own community.

“Systems will fail you, they can fail you,” Zuccaro said. “Instead of waiting for a system to understand how to service and learn how to service, maybe we’ll do better. Just by serving ourselves and trying to create our own systems.”

And this is just what Zuccaro and his colleagues at Latinx strive to do.

On March 14, the Latinx Center broke ground on its Bilingual Early Education Center while its first interpreter training program (TICT) session kicked off on April 14. Just last year, the center translated over 268 hours of material and 169,604 words while also distributing 14,252 gallons of water to the culturally diverse Latin community that visits.

Beyond translational services, last year, the center oversaw 34 new LLCs from the Hispanic community and over 68 people became fully employed. “I think the exciting part is not only maybe staying in that labor force but now taking agency and becoming the business owner in that labor force,” Zuccaro said.

A spot of pride for the center is the over 20 competitive applications they have received for the Youth Leadership program, which enlists local youth to beautify the east side, encouraging reinvestment within the Hispanic and immigrant communities.

And that revitalization takes shape in the form of new arrivals, as the city’s east side now crackles with sanguinity these 10 years later. In the face of the general population’s 1.6% decline in 2021, Genesee County’s immigrant population jumped to approximately 11,269 with most journeying from Cuba, Mexico, India, Iraq and Venezuela. Much of the community is attracted to the low property values and cost of living within the county and specifically in Flint, which is a remnant of the crisis.

“When they come here, it’s warm for them. They feel like family members too,” said Devianise Padilla Borgos, the advancement coordinator for the Latinx Center. “If they’re new in the community, they know this is the first spot.”

A similar thread of communal ambition and advancement dances about the mosaics of stained glass and the worn wooden pews of Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church.

For long-time Flint resident and one of the hands who helped build this Latin church from the ground, 84 year-old Lucia Pacheco sees attending as a matter of survival.

“The church is keeping the Mexican, the Spanish-speaking people together. Otherwise, we wouldn’t see, we wouldn’t see a thing,” said Pacheco with a contagious force in her voice. Despite her diagnosis with stiff person syndrome, a rare neurological disorder that causes intense muscle spasms, she and her husband Vincent walk through the doors of the church every Sunday.

Even more than 10 years on, the halls of the San Juan Diego Activity Center are still overflowing with food donations and volunteers continue to distribute free bananas, milk and most importantly, cases of water to a sidelined but tenacious community.

“I just feel that we all have a purpose in life,” Sauceda said, her face softening at the sound of a beautiful mélange of Spanish and English. “And it can’t be just sitting on your hands and doing nothing.”