The People

Flint Made

An oral history of identity,

endurance and adaptation

Photos and text

by Claire Adner

The People Flint Made

An oral history of identity, endurance and adaptation

Photos and text

by Claire Adner

FLINT - The water crisis didn’t just poison bodies. It rerouted lives, upended routines and redefined identities. It turned parents into protesters. Scientists into whistleblowers. Neighbors into warriors. Artists into organizers. Flint is not just a story about contamination, it’s a story about adaptation.

The crisis began in 2014, when Flint’s drinking water source was switched from Detroit’s system to the Flint River in a cost-cutting move while the city was under state-appointed emergency management. The river water wasn’t properly treated, allowing lead from aging pipes to leach into the community’s drinking water. Residents quickly noticed the difference – brown water, rashes, strange smells – but for over a year, officials dismissed their concerns. By the time the government acknowledged the problem, thousands of people had been exposed to lead and other contaminants. Trust in public institutions collapsed and, in its place, a network of ordinary people stepped up to do what officials would not.

The following roles don’t define the people who took them on, but they reveal new dimensions of them. For some, it meant filing FOIAs, collecting samples and raising the alarm. For others, it meant listening harder, asking questions, refusing to be reassured. When trust in the system dissolved, what emerged was something fierce and unrelenting. Not because people wanted to be watchdogs – but because they didn’t have a choice.

The Water Watchers

Some people never stopped focusing on the water itself. Whether tracking what comes out of the tap, pushing for better infrastructure, or continuing to ask basic questions about safety, for them the water crisis didn’t end, even when it stopped being news.

Elin Betanzo

Elin Betanzo is a water engineer with firsthand knowledge of what happens when corrosive water is pumped through old lead pipes. A former EPA official, she lived through the Washington, D.C. lead crisis in the early 2000s, where thousands of residents were exposed to dangerous lead levels due to similar regulatory failures. So when Flint made the decision in 2014 to switch its water supply to the Flint River without implementing proper corrosion control, Betanzo recognized the risk immediately.

“The second they switched the water in Flint is when I thought - there’s potential for a problem.”

But she wasn’t in Flint. At the time, Betanzo was living on the other end of the state, watching from afar as warning signs appeared and were dismissed. She reconnected with her old friend Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, a Flint pediatrician, and encouraged her to analyze blood-lead data in children.

“Everything I experienced was as an outsider, with enough knowledge to know what’s happening, but no connections. Just completely frustrated. What can I do to make someone pay attention to the tragedy unfolding here?”

In the years since, Betanzo has dedicated herself to national reform efforts, advocating for stronger federal rules and helping cities build the technical capacity to safely replace lead lines. Flint may have ignited a national conversation but, as she emphasizes, technical fixes alone aren’t enough. The crisis was as much about governance as it was about infrastructure.

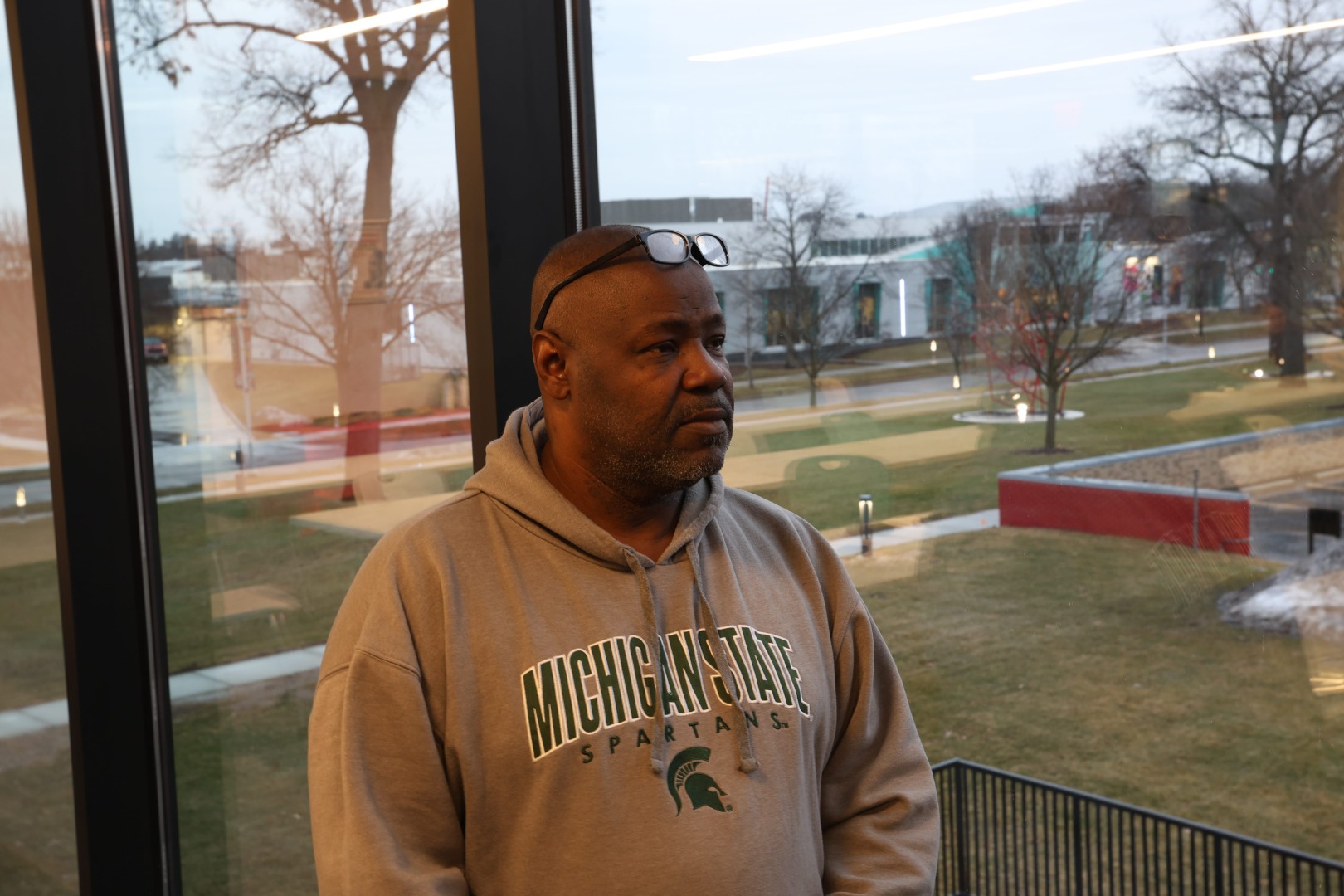

Scott Dungee

As the water plant supervisor in Flint, Scott Dungee lived through the crisis from the inside. He was there when the city, under a state-appointed emergency manager, switched its water supply in 2014 from Detroit’s Lake Huron-fed system to the long-defunct Flint River plant, a facility that had sat idle for years and required at least $50 million in upgrades to be safely operational. Instead, the state allocated just $4 million. The plant reopened anyway.

Dungee and his team were given 30 days to begin delivering water from a source that was known to be chemically unstable and they were largely untrained for what they were being asked to do.

“It’s heart-dropping. When you know you’ve got to make water in 30 days, and you’re scared to, but you’ve got no choice. So, you either quit… or you make the water.”

What followed became the national scandal: improperly treated water corroded aging pipes, leaching lead into thousands of homes. Trust in the water system collapsed. Now, years later, Dungee is still at the plant, helping to rebuild both the infrastructure and the public’s faith. His team continues work to recoat and restore damaged pipes, and he’s personally led efforts to bring residents back into the process.

“A lot of them still don't trust us, but at least try. Ever since 2017 we put that open door policy out there… I've had a few that totally don't trust it and within a year's time I've tested their water four or five times and they're on my side now. So I have made some headway.”

Karen Weaver

Karen Weaver became mayor of Flint in 2015, at the height of the water crisis. A clinical psychologist by training, Weaver had no political background, but ran on a platform of transparency and accountability and won, becoming the first woman to hold the office. One of her top priorities was replacing the city’s lead service lines. But for Weaver, the work that needed to be done was a chance to repair trust with the community.

“The first $30 million that we got, we hired three companies. Two were from Flint, one was from Genesee County… It was 2016, you know, Flint is a predominantly Black city—and it was the first time that a Black company had ever gotten a multimillion-dollar contract from the city of Flint.”

To Weaver, rebuilding the water system meant ensuring that the people most affected by the crisis had a role in repairing the damage. Her administration launched the Fast Start program, aimed at jumpstarting pipe replacement efforts quickly while hiring local contractors and workers.

“We said we need to hire people right from Flint, we need to see people that we know doing this and give people in Flint an opportunity, because that was going to be part of our healing too was taking care of ourselves.”

The Relentless

In the long aftermath of the water crisis, some people found themselves stepping into the spotlight – giving testimony, leading protests and grabbing headlines. For others, the response was more local and constant. Neighbors who stayed, city workers who held the line and teachers who kept things going, experiencing the crisis at home but still showing up for their community.

Their work held the community together, and when the cameras packed up and moved on, this strength didn’t fade, it remained relentless.

Claudia Perkins

For Claudia Perkins, leader of the bargaining unit of the United All Workers organization for nearly 30 years, fighting for justice isn’t new. So when the Flint water crisis began, she didn’t wait to act.

“We had rashes in our face, on our legs, hair falling out, all of those things. And so we knew we had to do something. So we all came together and we met and we talked and we formed the group, Democracy Defense League.”

The Democracy Defense League quickly became one of the loudest grassroots voices holding officials accountable. Made up of local residents and labor organizers, the group’s members organized protests, attended public hearings and ensured that Flint stayed in the national spotlight.

“I’m not missing one court hearing. We're there in full force… we go, we listen, if we have to testify, we do that. We fight to win.”

Lily Wilson

The Flint water crisis exposed more than 30,000 children to elevated levels of lead, a neurotoxin that can cause developmental delays, learning disabilities, behavioral issues and problems with memory and attention. Researchers have documented spikes in special education enrollment and a rise in anxiety and emotional dysregulation among Flint’s youth in the years following the switch to contaminated water. Like many educators in the city, Lily Wilson carries the weight of a crisis that began outside the classroom but shows up inside it every day.

“When the kids come to school and they have an issue, we're there to help in any way, shape or form. And what we can't do, we go to the next person that can help. So it's all about outreach and stretching and making sure that the need is met.”

Wilson says her role goes far beyond teaching, supporting students not just academically but emotionally and physically. The community’s trust in institutions was shaken, but schools remained one of the few reliable spaces where families could turn for help.

“It shifted the identity of the community…it takes a village to raise that kind of hope back to get it back to where it needs to be and to bring something new…I feel like I became much more resilient.”

Christian Perkins

For Christian Perkins, a firefighter and safety training officer with the Flint Fire Department, the water crisis reshaped every aspect of life.

“I'm dealing with the water crisis personally. And then I go to work and it is the biggest thing - not fires, not EMS costs - the biggest thing that we were dealing with at that point was the water crisis.”

Fires and medical calls didn’t change much, but as lead levels in the water became a national scandal, the fire stations transformed into logistical hubs for emergency response. The city’s firehouses were repurposed as water distribution centers, and local firefighters were asked to help coordinate with outside agencies to serve thousands of residents in urgent need of clean water. During the peak of the crisis, when federal resources were deployed to assist in distributing bottled water and filters, the fire stations became key access points for that effort.

“They brought in the National Guard and the National Guard used our stations as a point of delivery to the citizens. Go outside and you'd have hundreds of cars lined up to come and get water.”

And when the aid left and the cameras turned away, it was Flint residents like Firefighter Perkins who continued to carry the community forward.

“It felt like everybody just packed up their tents and left. And we were left to deal with it as we've always had to deal with things – just trying to come together as a community and work it out amongst ourselves.”

The Messengers

As advisors and advocates, the crisis pushed some outward, turning local pain into national purpose.

Amber Hasan

For Amber Hasan, an artist and advocate, the crisis changed her work and focus.

“When the water crisis happened, it opened my eyes to so many of the environmental injustices and how they intersect with race and gender and socioeconomics. How easy it is in the first world to end up without the resources necessary to live just a regular life. And it happened to my community. My eyes were opened to how it was happening in so many other communities in the United States.”

As she watched the fallout unfold, Hasan began drawing connections between Flint and other-income communities across the U.S. where water access, environmental neglect and institutional failure often collided. Her response was to create and to organize. In 2016, Hasan co-founded The Sister Tour, a traveling artist collective and media platform dedicated to connecting and lifting up the stories of marginalized women and communities through performance, workshops, mutual aid and digital storytelling. What started as a creative collaboration quickly evolved into a national network of artists and organizers, using art to speak truth and build solidarity across geographies.

“I think that the role of artists is to tell the truth…you use whatever tools you have” … for us with the sister tour, it is our network. It's the people that we know and who know us and who trust us to do the work that we do. It is being able to have a voice through being an artist and being able to speak to people in a different way.”

Elin Betanzo

The Flint water crisis became a turning point in how the country talks about drinking water. Since her role in exposing the crisis, Elin Betanzo has become a leading voice in national water policy and lead line replacement efforts.

“It's changed the fundamental conversation…it’s the first time ever we have $15 billion to fund replacement of lead service lines, under the Biden administration that was the first time a single dollar had been allocated for getting rid of lead service lines. So from that perspective Flint has changed everything about how we talk about prioritizing the issue of lead and drinking water.”

But while the funding is a big step forward, implementation remains a challenge. An estimated 9 million lead service lines are still in use across the United States, many of them concentrated in older, low-income and majority-minority communities. Replacing them is a massive logistical and financial undertaking. The Environmental Protection Agency has set a goal of removing all lead service lines within 10 years, but many experts and advocates believe that without stronger oversight and coordination, the timeline could stretch much longer.

“Collaborations and partnerships are critical to making any progress with this, ‘cause there is no way to fight against the establishment alone…we are up against the industry, we are up against the whole establishment of those who are supposed to be providing public health and protection and are fighting against it every day.”

Karen Weaver

Even after leaving office in 2019, Weaver has remained a vocal advocate.

“The story of Flint needs to stay in the national spotlight, because this is bigger than Flint.”

What happened in Flint can, and does, happen elsewhere. And the most powerful tool communities have, she says, is their voice.

“We’re fighters and we’re proud of it…our voice has been our greatest asset because we don’t go away and we continue to talk about it.”

The Builders

Sometimes waiting for things to be fixed isn’t an option or takes too long. For many in Flint, they kept building anyway. Painting murals. Opening studios. Starting businesses. They're not denying what happened, they’re just refusing to let that be the only story.

Kelly Martin

For Kelly Martin, a tattoo artist who recently opened a studio in downtown Flint, her city is so much more than the water crisis.

“Anywhere I go that's the only thing they want to talk about. There's just, how's the water? Is it kind of like, are you kidding? We're like, ‘no, it's not fixed.’ It's broken here, we're all, like, still struggling. But that's just one thing out of the, like, things that's happened…I’m more like, look at this city rising…that’s what’s really important to us”

Her friend and fellow artist, Pauly Everett, agrees.

Pauly Everett

Everett, a Flint-born street artist and muralist, has been painting long before the water crisis. His work, often vibrant and community-focused, is part of a broader creative movement that’s taken root in Flint over the past two decades: artists reclaiming walls, alleys and abandoned spaces to tell a different story about their city.

“We all just get together and help each other out…People look out for each other and we both do tough times and help each other out.”

As a street artist, Pauly was active before, during and after the water crisis.

“When Flint comes up in a conversation, we want them to think of the art we're making. You know, I mean, the cool thing we're doing, the creative things we're doing. Yeah. From rocking to throwing gallery shows. I mean, we're traveling the world and making art.”

James Moore

James Moore, a Flint resident and entrepreneur, sees opportunity where others see decline. His message is simple: don’t wait for someone else to fix it – build it yourself.

“I'm an entrepreneur. I really stress on we have to make things happen for ourselves.”

For Moore, revitalization doesn’t depend on looking back and wishing the past had gone differently, it’s about building a new future with what the community has now.

“If the big companies won't come, then we got to do grassroots and go Fortune 500 from within. We can't hide behind excuses on why we can't do it. We got to come up there. We can do it. We used to build carriages and wagons here and we started building cars and trucks and we're moving on even more into the future. So we got to do more thinking outside of the box on things that we can do.”

Flint never disappeared. It’s just been underestimated.

“A lot people say Flint will never come back. I said, Flint never left. It is always here. We didn't cut the lights off.”

The People Flint Made

An oral history of identity, endurance and adaptation

The story of Flint is not over. In a city where trust was broken, what endures is not just resilience, but reinvention and people who refuse to let one disaster define them. The stories are not neat and are not resolved, but they demonstrate what happens when ordinary people are asked to carry extraordinary weight and how, in the face of failure, they keep finding ways to build, to push and to stay. In Flint, the future is still unfolding – in classrooms, on sidewalks, in council chambers and tattoo shops – one conversation, one mural, one water test at a time.