FLINT — Bethany Hazard believes she will die before anyone is held accountable for the poisoning of Flint’s water.

In the decade since lead and other contaminants infiltrated the city’s water supply and set off the country’s largest man-made public health disaster, Hazard and thousands of others have watched criminal charges against state officials fail to see a day in court and promised settlement money stall in its disbursement.

The 68-year-old has battled two rounds of cancer and an immune system disorder, which she partially attributes to the discolored water that flooded from her faucets during the water crisis. Today, she spends her days at home, devoid of hope that anything will change.

“We’re disposable people, we don’t matter, that’s all. It doesn’t matter what happens to us here,” she said between sips of coffee held between weathered hands. “There’s no democracy here. They don’t think about the people, they’re thinking about how much money they can get.”

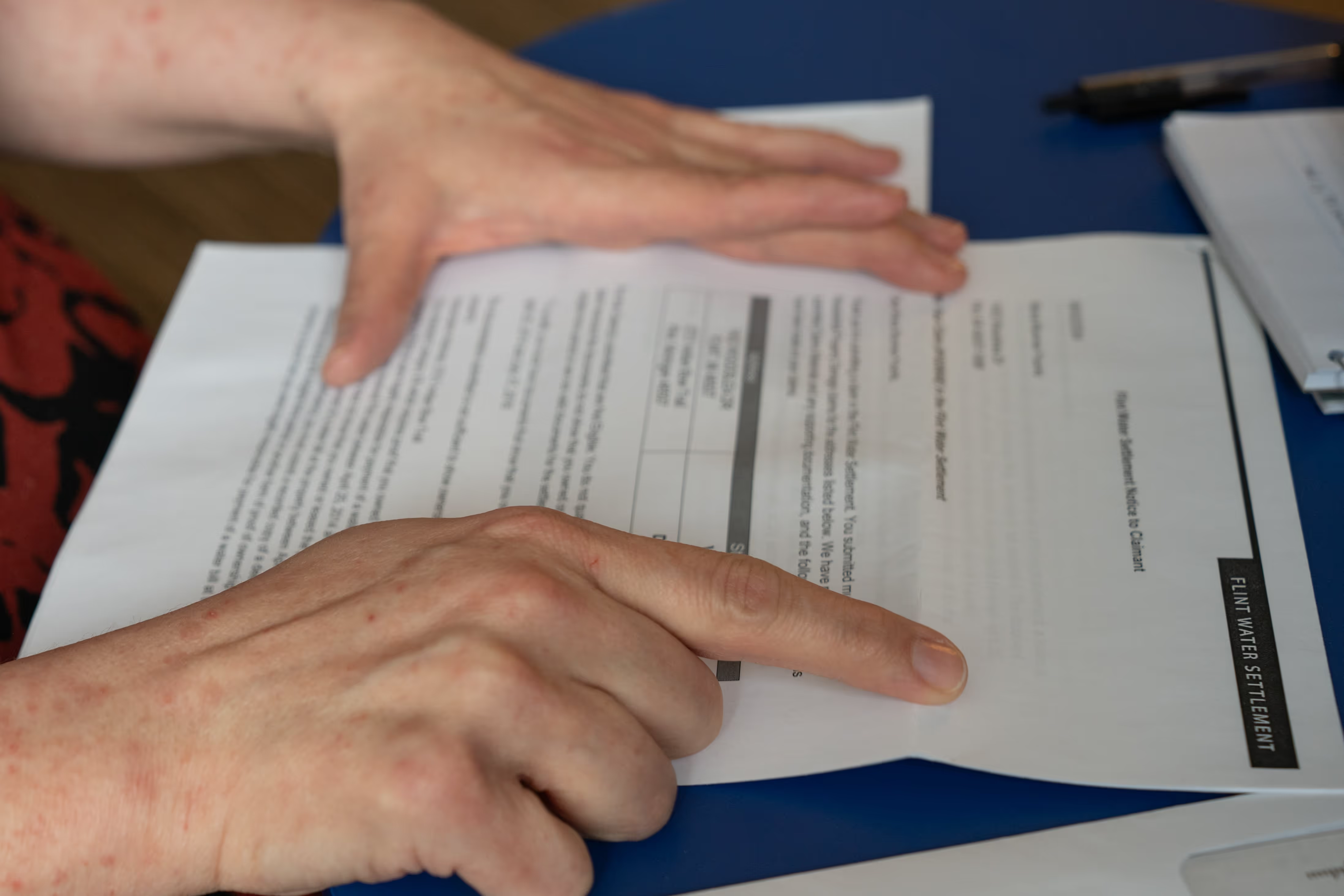

Even though a historic $626 million settlement was approved in United States District Court in 2021, the process for earning a spot was riddled with complicated paperwork, requiring people to prove that their devastating illnesses and injuries resulted from the tainted water. As of early January, 27,581 claims had been approved, which is about one-third of Flint’s population. Not one claimant has been issued a penny so far, while lawyers have been awarded three rounds of payments that total in the millions.

On many fronts, the people of Flint feel there has been a complete lack of accountability taken in the aftermath of the water crisis. They have spent endless amounts of money on doctors’ appointments, medications and bottled water that is safe to drink, all the while desperately waiting to see anyone held responsible for the tragedy brought upon their city. In 2023, Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel called off her office’s pursuit to prosecute former Gov. Rick Snyder and other top officials after the state’s Supreme Court dismissed the charges.

When Nessel’s office first partnered with Wayne County Prosecutor Kym Worthy and Michigan’s Solicitor General Fadwa Hammoud in 2019 to bring prosecution against Snyder and 15 other officials, Hazard thought maybe something would come from it. After all, the team vowed to exhaust “all available legal options” when Nessel dropped the cases her Republican predecessor, Bill Schuette, had previously been litigating.

Schuette had charged 15 state and local officials, including emergency managers and a member of the governor’s cabinet, with crimes as severe as involuntary manslaughter. Though seven had already taken plea deals and eight more were awaiting trial, Nessel wanted to start from scratch.

But after four years, Nessel put the effort to bed when Michigan’s Supreme Court ruled that the officials had been improperly indicted under a longstanding state law that allows a one-man jury to investigate, subpoena witnesses and issue arrest warrants, but not hand down indictments.

“When [Nessel’s team] came here I met with them and they said they were going to make us whole. It was just a big, fat lie. So what can you do?” said Hazard, who worked at the Veterans Hospital for 27 years before she was forced into early retirement due to her illnesses. “There’s no justice; there never will be.”

Breaking down the settlement

On Nov. 10, 2021, Judge Judith Levy of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan granted final approval to a historic $626.25 million settlement resulting from the combination of several class action and individual lawsuits brought on behalf of Flint residents and businesses against multiple governmental defendants.

The state of Michigan is responsible for the majority of the settlement with a $600 million payment. The city of Flint is paying $20 million, McLaren Hospitals $5 million and Rowe Professional Services Co., which did engineering work related to the 2014 switch to the Flint River as the city’s drinking water source, is paying $1.25 million.

Because some of the most lasting effects of the poisoning were a result of high lead levels, about 80% of the funds will be dispersed to individuals who were under the age of 18 at the time of the crisis, with a large majority to be paid to children who were 6 and younger. The remaining funds will go to special education services in Genesee County, adults, business owners and property owners for property damage.

But under the terms of the settlement, no claimant is to be paid until all of the claims are fully resolved, including appeals. The deadline for all outstanding paperwork to be filed was the end of March, and the lawyers for the claimants said they expect payments to start this summer.

Eleven firms are presently involved in the settlement effort, though about a dozen more have had their hand in the pot throughout the years-long process, said Cary McGehee, a partner at Pitt McGehee Palmer Bonnani & Rivers, one of the two firms serving as co-lead counsel.

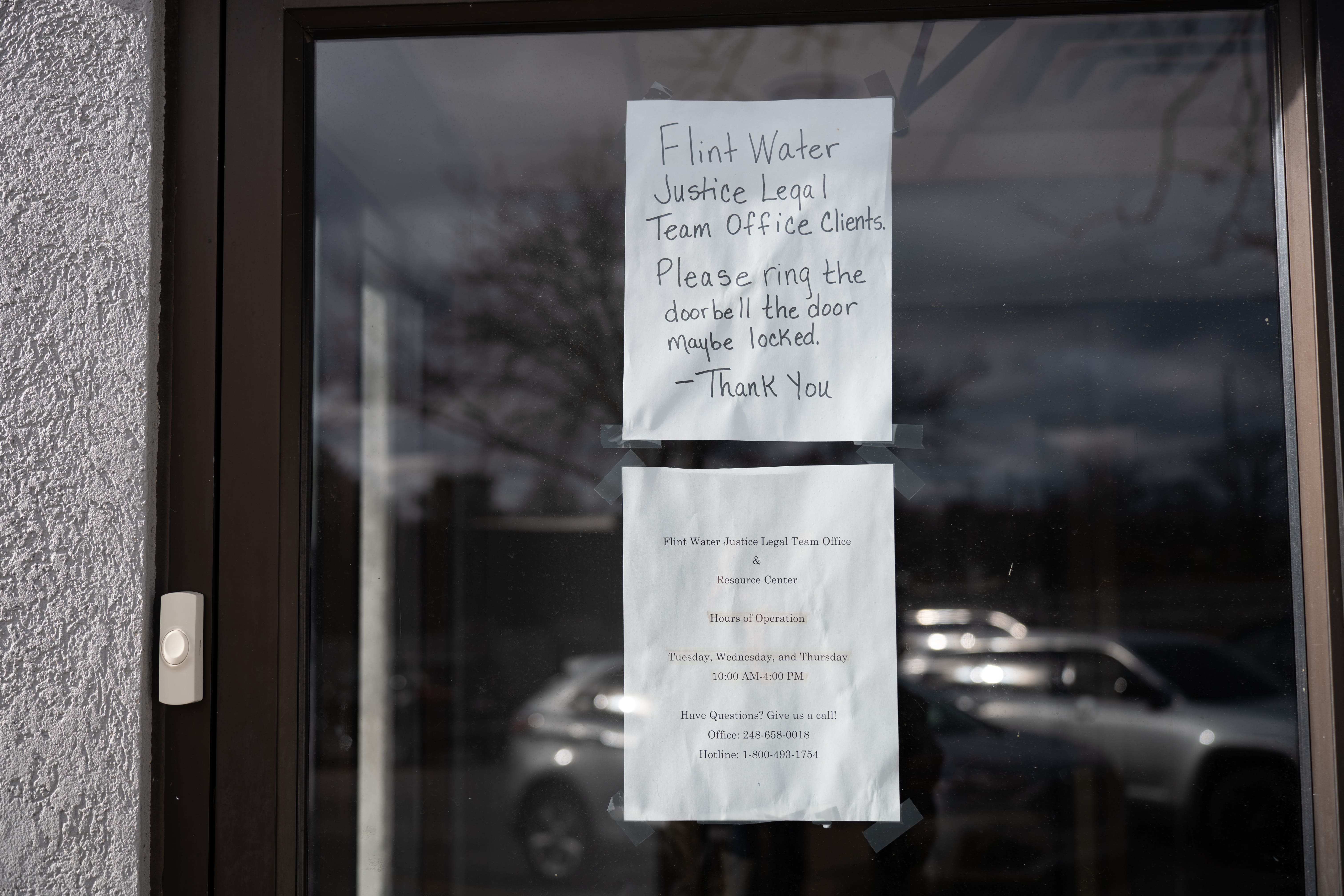

Behind a tinted glass door lies an office suite where a legal assistant works three days a week. Yellow notepads and piles of papers are stacked on her desk, a can of Dr. Pepper sits within arm’s reach.

On a Tuesday afternoon in early March, she patiently coached a Flint resident over the phone on how to locate their parents’ medical records and record the information onto paperwork to ensure that the correlation between their gastrointestinal disease and the tainted Flint water verified their claim to be part of the settlement. They were on the phone for about 15 minutes.

A second went by before she picked up the ringing phone again.

“Was your injury between 2014 and 2016?” she asked the next caller.

The small “Flint Water Crisis City Counsel Team” office, located in the back of a parking lot off Robert T. Longway Boulevard, is open three days a week from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. It’s where the two co-lead counsel firms encouraged their clients to stop by and ask questions about the paperwork they were asked to fill out.

Foot traffic leading into the office had nearly tripled in the weeks leading up to the mid-March deadline, said the woman, whose boss, one of the lawyers at Pitt McGehee Palmer Bonnani & Rivers, told her she was not authorized to speak with reporters.

In the past year, the settlement pool has increased by $33 million due to two engineering companies agreeing to settle over allegedly failing to give appropriate professional advice to prevent the flow of lead into Flint’s drinking water.

Final approval to the $8 million settlement against Lockwood, Andrews & Newman, an engineering firm based in Texas, came in May 2024. In October, final approval was granted to a $25 million settlement with Veolia North America, a Boston-based engineering company that the state said failed to properly identify corrosion control issues.

Veolia agreed in February to pay an additional $53 million to close out an eight-year long litigation process — money that is still under review to be added to the settlement fund.

But despite all the legal work in the process, those affected by the crisis have yet to be handed results in the form of financial compensation. Some lawyers also aren’t sure the end result will achieve as much justice for victims as initially believed.

“When you go into a process like this as a social justice-minded lawyer, you think you’re going to accomplish things, and in retrospect, I don’t know if that’s in fact what happened here,” said Julie Hurwitz, president and partner at Detroit-based firm Goodman Hurwitz & James, one of the litigating firms. “I think the community will never be made whole. I think the amount that each individual class member is going to get is miniscule compared to what they went through.”

It is unclear how much individual claimants will receive from the settlement. Lawyers said no one will know the amount they’re expected to receive until payment notices are issued, but the court has ruled that individual awards as low as $500 would be acceptable.

More than 28 law firms played a role in the development of the settlement, which also reduces the amount of money that will ultimately be dispersed to claimants. In a 2022 ruling, Judge Levy awarded the involved firms 31.33% of the total settlement fund, which includes a global “CBA,” or costs and benefits agreement, of $39,641,625 and an expense award of $7,147,802.36, for the resources the firms paid for.

In order for the court to rule on how much lawyers should be awarded, firms had to submit what’s known as lodestar documentation, a method of calculating attorneys’ fees by multiplying the hours employees worked by a reasonable hourly rate. For example, one partner put 36 minutes of work into the settlement. Under the lodestar calculation, he would be eligible to receive $534 at his hourly rate of $890.

Some claimants petitioned against the amount the lawyers asked to be paid.

“Plaintiffs’ attorneys are being paid too much and community residents are not receiving adequate compensation in view of the long-term harm the water crisis created. Plaintiffs’ attorneys will receive much more compensation than the average adult in the settlement,” anonymous objectors wrote in a court filing.

Their complaints were rejected. When Levy awarded the lawyers their compensation in 2022, she wrote that although she heard from many objectors, they represented an “exceedingly small” amount of people in comparison to the “overwhelming number of non-objecting participants.”

However, the court found that individual class settlement awards of approximately $500 per claimant are “substantial” awards and that a total attorney fee award of over $1 million is reasonable, according to one court filing.

EPA lawsuit

A major player in the water crisis was the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, which lawyers believe has evaded scrutiny for too long by hiding behind sovereign immunity, a legal doctrine that protects the government from being sued without its consent.

Litigation against the EPA has been in the works from Flint residents since 2016. Plaintiffs allege that the agency failed to utilize its enforcement authority under the Safe Drinking Water Act to intervene, investigate, obtain compliance and warn Flint residents of the health risks posed by the water.

The United States argues that it has not waived its immunity from plaintiffs’ claims because Michigan law would not impose liability on private individuals in similar circumstances—the extent to which the Federal Tort Claims Act, or FTCA, only waives government immunity—and because the alleged misconduct by the EPA is excepted from liability under the FTCA’s discretionary function exception.

But in February, Judge Linda V. Parker denied the agency’s motion to dismiss the lawsuit, writing in the decision: “While the EPA may have had the discretion in deciding when and how to respond to citizen complaints about Flint’s water, once it decided to respond, it did not have the discretion to provide dangerously misleading or inaccurate information.”

McGehee and Hurwitz are two of four firms that have been litigating the case against the agency. They have a glimmer of hope that the EPA’s time in court will soon be approaching.

“The EPA had the ultimate responsibility for overseeing that the water was safe, and they should’ve known at the time of the switch that the corrosion control hadn’t been administered and that it was going to result in leaching into the water,” Hurwitz said.

Two parallel cases are before Judge Parker for a bellwether trial, which is when a small consolidation of lawsuits are taken from a larger group of similar cases to be tried almost as a practice run for future cases.

McGehee and three other firms are representing roughly 8,000 individuals in the EPA case. The parallel case is brought on behalf of roughly 500 children, McGehee said. No sums have been discussed yet.

Judge Levy set that trial for January 2026. Flint residents and experts will have the opportunity to testify about the damage that was inflicted upon the city.

“Finally, the people of Flint will get their day in court,” McGehee said.

‘We’re still here’

Thousands of Flint residents who could afford to leave the city after the water crisis did. The city’s population dropped about 15% between 2015 and 2020.

But for Mike Herriman, who runs Vern’s Collision and Glass, an auto-repair shop in the city’s East Side, there’s no reason to give up on a place that’s been his home since the business began 53 years ago under his father’s direction.

“They’ll come here because we’re still here,” said Herriman, 72. “We’ve stuck it out.”

Herriman believes that the idea of accountability has become rooted in Flint’s identity in an adverse way. People became sick of seeing leadership fail to take responsibility for what happened and, as a result, many decided to give up on their own responsibilities, too.

He said this “snowball effect” has resulted in a loss of motivation for many Flint residents to pay taxes or water bills, keep up their homes or even take their cars in for repairs at his shop.

Herriman, who is involved in numerous neighborhood associations and advocacy groups, said the government should not be exempt from prosecution. The only way he feels the city can ever receive justice would be if officials are properly charged in court, which seems more unlikely than ever.

Nessel in 2024 said she would publicize the findings of her office’s investigation so the public would finally know of the corruption that occurred. But a few months into 2025, the investigation has still not been released.

“The Attorney General intends to publish this department’s report on the Flint Water Crisis investigation and prosecutions [later] this year,” Nessel’s press secretary, Danny Wimmer, wrote in a statement. “She continues to express her desire that the settlement funds be disbursed to the people of Flint as promptly as possible.”

For Claire McClinton, a longtime social justice warrior and founder of the Democracy Defense League, a group of Flint residents dedicated to fighting for democratic rights, Nessel’s decision to drop the prosecution was simply another hit on a community that has grown accustomed to being let down.

“We were already demoralized because nothing was happening. We're not going to act like the water is just like it was, but it’s not where it should be. And for them not to hold anyone accountable, was such a blow, I mean, it was just such a blow,” she said.

McClinton believes that Nessel didn’t do enough to push the prosecution forward, especially after making a show of firing special prosecutor Tod Flood, who reviewed millions of pages of discovery during his work for Schuette’s office.

“The charges being dropped was devastating to us,” she said. “And it could only be one or two things: either incompetence or treachery. You either sold out or you didn’t know what you were doing.”

McClinton and Herriman both said that nothing would materialistically change for Flint if officials were charged, but it would move mountains in boosting morale for a population that has continuously been lied to and deceived.

“The same organizations that lied to us back then are still in power and nobody’s been convicted. It proves to the community that we can’t trust the system,” Herriman said. “There’s still not been acknowledgement, there’s not been prosecution. Nobody has been able to say, ‘OK, they’re finally convicted and because of that, maybe no one will do it again.’”