FLINT — It was nine years later but Arthur Woodson, standing at Donaldson Boulevard on the north side of Flint, still remembered every detail of when he last visited this neighborhood to see his friend Pastella Smith.

“I call it the hot zone,” said Woodson, a community leader and lifelong Flint local as he walked up and down that same quiet road, pointing to the house where he learned his friend had multiple myeloma.

What struck Woodson that day in 2016 is that it wasn’t the first time he’d heard of the blood cancer that attacks antibody-producing cells. A former Army corporal, he knew of the uncommon disease because of its association with Marines and their families at Camp Lejeune who were exposed to contaminated water from the 1950s through ‘80s at the North Carolina military base.

Woodson, who, along with thousands of others was exposed to contaminated water in Flint, Michigan, in 2014, couldn’t let the coincidence go. He left his friend’s house and “knocked on 30 doors in a one-block radius. Just one block. And I found eight multiple myeloma cases.”

Then he walked down Brownell Boulevard, Wolcott Street, Concord Street and others through the city’s northside. Each had instances of this same cancer with just a driveway separating two of the affected on Brownell. Both of those neighbors have since died, as did his friend Pastella Smith in 2020 at 54 years old.

What Woodson seemingly stumbled upon is what epidemiologists have come to call a “disease cluster.” It’s a term used to describe an unusually large incidence of a relatively uncommon disease. Multiple myeloma affects about seven out of 100,000 people each year, yet as Woodson reckoned, the streets of north Flint were brimming with it.

“Are you serious?” he said in early March this year, frustrated that others still don’t see what he sees.

But Woodson isn’t the only person to feel outrage by the level of illness afflicting Flint residents. Others, including officials at the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) and even former Vice President Kamala Harris, also took note of the peculiarly high rate of cancers in Flint. That’s in part thanks to Woodson and community advocates like him. Because after years of attending public meetings, writing letters, knocking on doors and liaising with the Environmental Protection Agency, others did start to listen.

Tests and Testimonies

In February, it was announced that the local campus of Michigan State University would conduct the first phase of the cancer cluster study, also known as a “feasibility assessment,” which determines whether it is possible to conduct a full-scale epidemiological study.

Within this initial phase, experts will gauge both the extent to which data can be collected and community receptiveness to involvement in the study.

“Is it possible from a data standpoint? Can we get the data to indicate that there is some level of difference or some level of unusual pattern?” said Heather Uphold, a public health professor at Michigan State University’s Flint campus specializing in community-engaged dissemination, implementation science and improving data equity. She and her team are conducting the feasibility study.

As Uphold points out, there are numerous complications in establishing a connection between cancers and carcinogens in the environment because most scenarios are not simple correlations. After the fateful water switch from Lake Huron to the Flint River in 2014 and the subsequent corrosion control that led to the leaching of lead into water pipes, multiple conditions including a constellation of cancers presented among the population.

But what else has contributed to that, experts ask. In November of 2016, for example, elevated levels of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, also known as PFAS or “forever chemicals,” were discovered in the Coldwater Road Landfill, previously owned by General Motors prior to its declaration of bankruptcy in 2009. Three water samples taken at the time all exceeded federal drinking water standards for the chemical. Additional PFAS contamination was discovered in Gilkey Creek, a tributary of the Flint River, in late 2017. Known illnesses related to its presence include kidney, testicular and thyroid cancers.

However, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality conducted an investigation into the elevated levels of PFAS chemicals in the Flint River at the time and determined the results of its presence were inconclusive.

More recently, in December 2024, Michigan’s Department of Environmental Quality issued a notice to the city of Flint, citing occurrence of total trihalomethanes, or TTHMs, in violation of the Safe Drinking Water Act of 1976. TTHMs are disinfection byproducts that arise as a result of water chlorination and are suspected carcinogens, specifically in the case of bladder cancer.

“Trihalomethanes are considered carcinogenic in the case of bladder cancer only. We don’t know if they’re carcinogenic in terms of other types of cancer. . . . So, how far out into the community they actually go, we don’t know,” said Diana Haggerty, an epidemiologist and director of research for the Flint Registry, a non-profit that seeks to connect victims of lead poisoning from the water crisis to programs that promote health and wellness.

But again, as Haggerty pointed out, it’s very difficult to draw a straight line between polluted Flint River water and the illnesses Flint residents contract because there are so many environmental factors at play in the city.

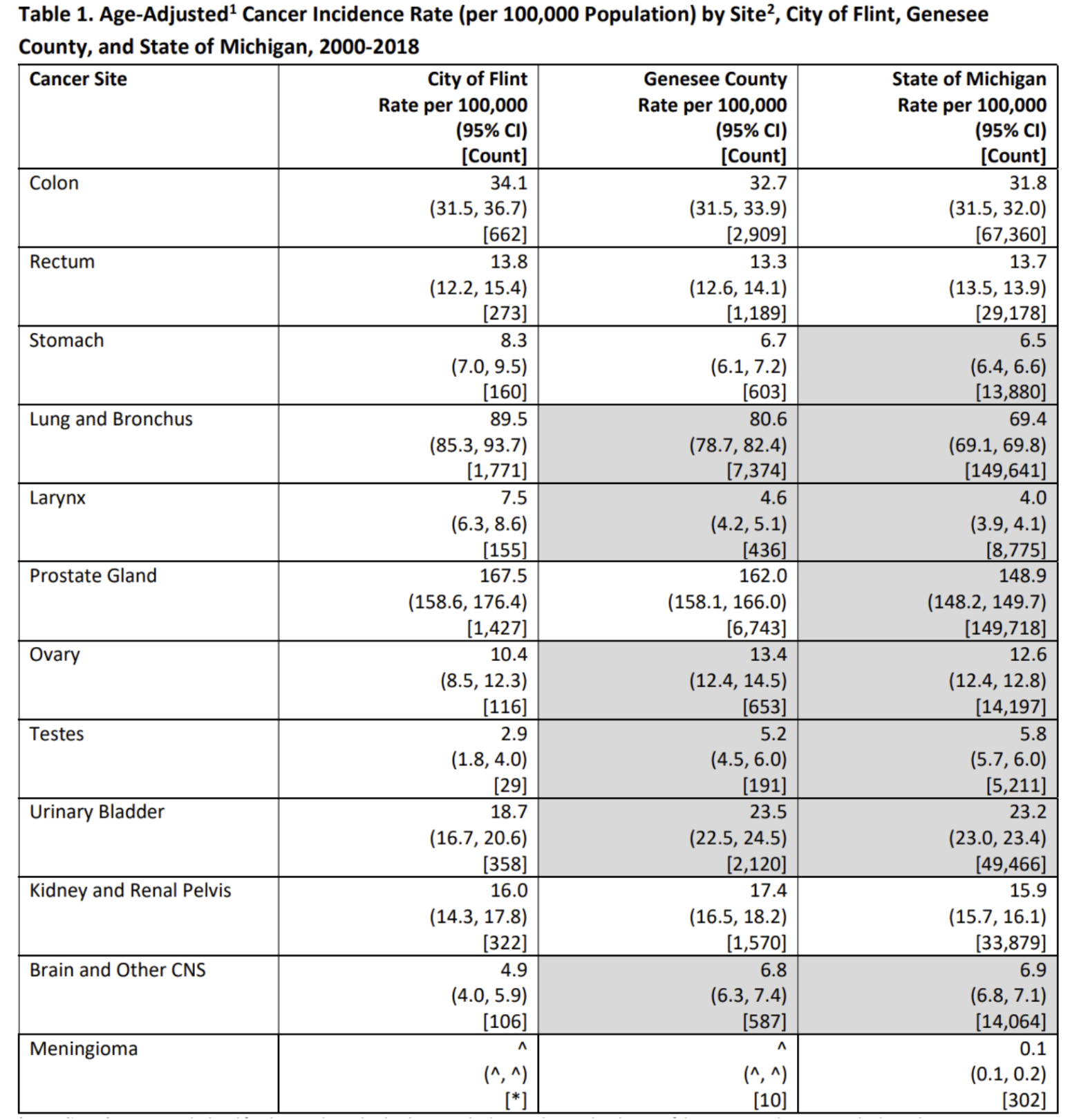

However, with cancer numbers escalating – and specifically aggressive and rare cancers showing up – the MDHHS published in May 2021 a Cancer Incidence Data Review covering the years of 2000 to 2018. It addressed incidence rates of cancer within the city of Flint in comparison to Genesee County and the state of Michigan at large.

According to the report, over the course of 19 years, Flint shows a significantly higher incidence of lung and bronchus cancer, larynx cancer, stomach cancer and prostate cancer as compared to Genesee County and the state of Michigan.

Ultimately, though, there was no conclusion indicating an increasing or decreasing trend in cancer rates within the city of Flint over the last 10 years specifically since the water crisis.

And, there are other complications with drawing correlations. “When you’re thinking about cancer and cancer diagnoses,” Haggarty said, “someone has to survive long enough to actually get a cancer diagnosis to be counted. . . . And there definitely could be people that we’ve lost, in terms of tracking the incidence of Flint, because they were healthy enough to move or maybe they were older and they passed away for other reasons.”

Poisoned or Paranoia?

Despite uncertainty surrounding the extent of exposure to toxins from Flint’s once-polluted drinking water, local residents are clear on this: high cancer incidence rates persist in their city.

“I’m the fourth person on the block to have cancer,” says Roy Fields, a 66 year-old Flint local and retired General Motors worker. “I’m the only one that’s still alive.”

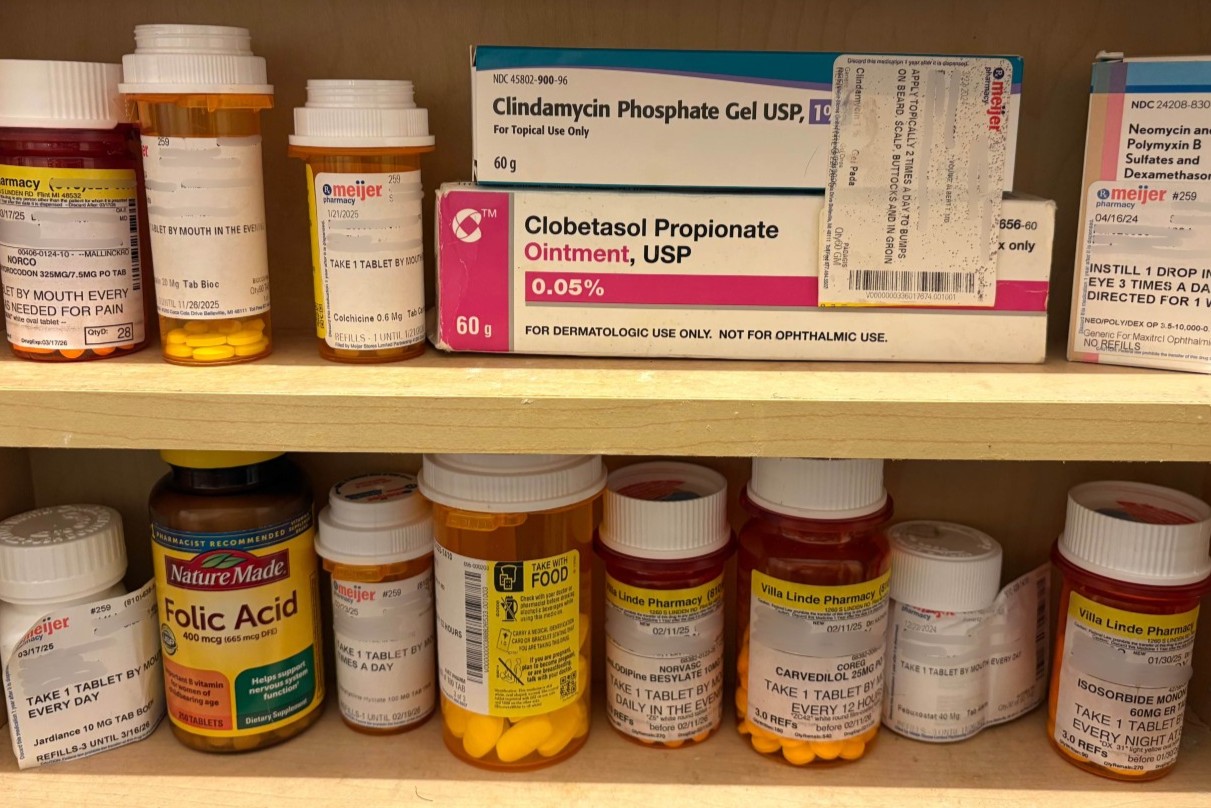

Losing his kidney to cancer last year, Fields has also been diagnosed with SAPHO syndrome, a rare autoinflammatory disease that leads to bone pain and reduced motor function, and hidradenitis suppurativa, a rare chronic, inflammatory skin condition that results in lesions and skin boils.

“If I go to a game, they had to help me up the stairs. My daughter hated to see me on my walker,” Fields said. “I could see the look in their eyes and stuff. And I still have problems, but I keep going.”

In the face of these diagnoses, Fields’ medicine cabinet has become a constant reminder of all that he manages.

As of early 2025, “they tripled the dosages of the medicine I take in order for me to survive,” he said.

Even though the city of Flint has met state and federal standards for lead and copper since 2016, Fields, like many residents, has not taken even a sip of Flint water since 2015.

“Is this a cause of, you know, what my body’s gone through because of the water? Is it?” Fields asked.

Woodson wonders the same thing every day.

“My cousin had three different cancers,” Woodson said of his 36-year-old cousin Mary Watson, whom he drove back-and-forth between University of Michigan Hospital in Ann Arbor and City of Hope Cancer Center Chicago in Zion, Illinois. “She was like, ‘Arthur, I don’t want to die. I want to be a lawyer, I want to write music. . . . I got a whole life to live.’”

Mary died in August 2018. Two months later, her mother Margaret Wesley was diagnosed with cancer.

“They found three spots on her brain, one spot on her lung, colon cancer came back, liver cancer, she had five different cancers, and they told her that she only had 18 months to live,” Woodson said about his aunt. She died in August 2020.

A Chance for Answers

Around that same time, Woodson was able to get an audience with then-vice presidential candidate Kamala Harris, who was coming through town on a campaign tour with husband Doug Emhoff. They both listened to his story – and promised that their eyes would stay on Flint if Biden and Harris were elected.

Soon enough, as part of a promise to revive the Cancer Moonshot Initiative that was launched under former President Barack Obama, President Joe Biden declared two national goals in 2022: to slash the cancer death rate in half by 2047 and improve the national standard of care for those living with cancer.

Woodson connected with Dr. Daniel Conerval, deputy chief of the Cancer Moonshot Initiative, and public health professors from Michigan State University to further raise awareness about the emerging patterns of multiple cancers in Flint.

That same year, the White House designated the National Minority Quality Forum (NMQF), the largest health equity organization in the nation, to address the disproportionate incidence rates within the city. In the same vein, the Flint Cancer Community Consortium, or FC3, was informally established with the ultimate purpose of “prioritizing community voice and responding to the cancer needs in the Flint community,” said Uphold, the public health professor at MSU.

A goal of all three initiatives was to get answers for the people of Flint.

“Getting this cancer study launched in the first place was a battle, a real battle for the community,” said Adjoa Kyerematen, vice president of communications and public affairs for NMQF, commenting on the back-and-forth of getting “any attention from government officials because of the implications of acknowledging the role of the water crisis in connection to elevated cancer risk.”

Money was also an issue. “Not many entities applied to facilitate this project because there wasn’t really a lot of funding in order to do this project,” added Kyerematen. Despite the hurdles, almost three years later, the process is finally moving forward.

“So for us, this is almost an investment in Flint,” Kyerematen added, “in ensuring that this cancer feasibility study occurs and happens.”

Woodson is frustrated that it took more than 10 years to see movement on a cancer cluster study, but he takes pride in his part of getting it underway.

“I don’t want them out here on the street singing kumbaya songs and holding hands, asking people and begging people to help them when it’s something that we should have took care of right then and there,” said Woodson of generations of contamination victims in Flint. “So I’m hell-bent on making sure that this is accomplished and that we put things in place for the future, for the kids and the adults to come.”